Our author, Clara Legallais-Moha, has shared her unique impressions of a journey to the heart of Kyrgyzstan. Enjoy the read! You can also check out her previous article on how to prepare for travel in Central Asia here.

Clara Legallais-Moha, city — Newbury, Travel Content Creator, French Language Coach, Actress, @clara_legallais, LinkedIn

Located in the Ferghana Valley, just a few miles from the Uzbek border, lies Osh, Kyrgyzstan’s second- largest city, home to around 300 000 people. About an hour’s drive from Osh, the valleys of the Alai Mountains offer stunning green and wild landscapes, surrounded by towering rocky peaks and dotted with yurts belonging to nomadic people, whose horses roam freely through the vast meadows.

Osh – Part I: Stifling Heat and Sacred Mountain

Tuesday 12th July 2022, Osh

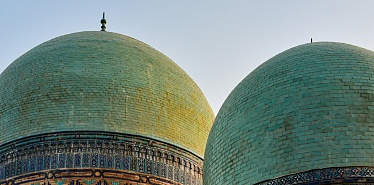

For 400 soms — £3.6, I buy a local SIM card from a mobile operator recommended by my taxi driver, then head to the Sulaiman-Too Sacred Mountain, a UNESCO World Heritage Site. For centuries, the five-peaked mountain has been a pilgrimage site for Muslims, as it is believed that the Prophet Muhamad once prayed there. The mountain’s many caves and crevasses are said to hold medicinal and spiritual power, including the famed fertility cave.

Halfway up, drenched in sweat and parched, I stop to visit the National Historical and Archaeological Museum Complex Sulayman, carved into the mountain itself. The museum is a bit overpriced and underwhelming, but the main goal is to catch my breath and enjoy some fresh air before continuing. A young woman from the tourist police asks to take a photo with me. Caught off guard and slightly uneasy, I pose beside her as her colleague snaps the photo. Fifteen minutes later, I reach the summit of Sulaiman-Too, rewarded with a stunning 360-degree view of Osh, a city peppered with trees.

I spend the late afternoon and evening wandering the streets of Osh and in Toktogul Park. At the entrance of the park, Lenin, with his right arm raised, greets visitors. Unlike in Uzbekistan, Lenin statues weren’t dismantled after the country’s independence in 1991.

Toward Tepchi Yurt Camp

Wednesday 13th July 2022, Osh

I put on my backpack and walk up to the Community-Based Tourism office of Osh Alai. There, I meet Zabeen, a Zambian woman in her thirties, with whom I would soon forge a strong bond during our three-day horse trek in the Alai Mountains. After some paperwork and organising our bags, the two of us, our guide Symbatek, and the driver jump into a pick-up truck. An hour later, at a curve in the road, a shepherd is waiting for us with three horses.

The path gradually climbs through the valley. Soon, we have some unexpected company: curious donkeys approach us and wild horses call out to our mounts, causing our horses to become tense and uneasy. A strong beige stallion has his front legs bound closely together to prevent him from attacking others. The sun is high in the sky, casting its light across the valley. The air is fresh and the noise of civilisation far behind us. Four hours later, we leave the rocky valley behind and arrive at the green summer pastures and Tepchi Yurt Camp.

Nestled between two mountains, the camp is home to several families, including our host’s. Although the stunning landscape is reminiscent of the Alps, it is unmistakably the land of the Kyrgyz nomads. Between the yurts, animals wander freely. Horses gallop across the meadows, cows are gently milked by their owner — though Zabeen and I gave it a try without much success, and the region’s plump-tailed sheep are herded into an enclosure for the night. Smaller animals, like hens, chicks, and turkeys with their young, also roam around, with the chicks huddling together to keep warm. In reality, those we call “nomads” are only semi-nomadic: they live in the pastures from June to September to graze their animals, but spend the rest of the year in nearby villages.

The yurt is welcoming, with thick, colourful carpets that would later serve as our bedding. A coal stove with a chimney running through the roof would keep us warm at night. The bathroom is nothing more than a hole in the ground, shielded on three sides by wooden planks! With no shower, we hand-wash our faces with soap and water from an outdoor tap.

The weathered face of our host, who appears older than she actually is, gives a glimpse into the harshness of nomadic life. We don’t have much conversation with the family, despite Symbatek acting as our interpreter. Our host is busy looking after her animals, her children, and the guests. After a warm dinner of soup, cream, and borsok – a kind of fried dough that tastes like a donut –, Zabeen and I settle into the yurt, while Symbatek sleeps outside in a tent.

Crossing the Sary Oï Valley via Airy Bell Pass

Thursday 14th July 2022, somewhere in the Alai Mountains

After a breakfast of bread, cream, and a large bowl of porridge, we set off toward the other side of the mountain. The climb is tough on the horses, and the descent isn’t much easier, as they have to tread carefully to avoid slipping. We pause only once for lunch in the shade of a large tree.

A few hours later, after following a trail that is unfortunately littered with waste from both tourists and locals, we arrive at the second camp. This camp is run by a woman with her five daughters, all under the age of eighteen, along with a cousin. Zabeen and I observe the milking of cows and mares. Using a hand-operated machine, the cow’s milk is separated into a creamy part and a milkier part. The creamy portion is eaten fresh, while the milk is used to make kurut, a type of fermented cheese that forms hard balls and dries in the sun.

Symbatek explains that the nomads never slaughter their animals; instead, they sell them and buy meat at the village market, along with other essentials like vegetables, oil, and flour. The meat is then preserved by drying it with salt. My favourite Kyrgyz dish is kattama, a fried bread that resembles a rich, flaky pastry. Zabeen and I feel more welcomed here than at Tepchi Yurt Camp, and this camp is more modern: unlike our previous hosts, this family lives in a cement house, which has a shower, Turkish toilets, and even a men’s urinal located just behind it.

For dinner, we enjoy plov, the traditional Central Asian dish made with rice, beef, carrots, onions, garlic, sheep fat, and sunflower oil. The family organises a small party for us. Two of the daughters sing and play the komuz, a traditional three-stinged instrument that resembles a small guitar. Under the starry sky, we all dance to Kyrgyz songs playing through a large speaker. A warm summer night, music, and a touch of spontaneity are enough to overcome the last barriers of language, culture, and religion.

Osh – Part II: Discovering Osh with Ainura

Sunday 17th July 2022, Osh

I meet Ainura near Muminovoiv Guesthouse. In her early forties and exuding elegance, she’s known as the best guide in Osh. She has a round and pale face with a jet-black hair cut in a bob. Ainura is divorced and raises her 10-year-old son on her own. Before I can ask about her country, she brings up Ala Kachuu, a dramatic practice where a woman or girl is kidnapped by her future groom. One of her close friends was a victim of this tradition, which was widespread during the Soviet era and, unfortunately, still persists today.

We walk to Osh’s only Russian Orthodox church, painted a vibrant blue, then cross the Ak-Buura River, which divides the city in two. We hop on a bus heading to the Jayma bazaar, where the lively covered market overflows with food, spices, and “Made in China” clothes. One store catches my eye — it sells cribs that come with a narrow wooden pipe used as a urinal. There are two versions: one for boys and one for girls. “People usually buy both”, Ainura explains, “because they assume if they have a boy, the next child will be a girl”. An entire section of the bazaar is dedicated to plants and seeds, while two teenage boys play snooker nearby. At the back, there is an open-air area where men work with metals and alloys. As we leave, Ainura glances at couches displayed on the pavement. We stop for lunch at a local restaurant before taking a bus to Uzgen, a town an hour drive north of Osh.

In the late afternoon, Ainura invites me to her home for tea. Despite the drab appearance of her multi- story cement building, her flat is warm and immaculate. While she showers, I glance at her many diplomas, certifications, and trophies displayed in a wooden bookcase in the living room, which also doubles as her bedroom. By the window, thick and colourful carpets are stacked nearly to the ceiling. Every night, Ainura and her son unroll these carpets to sleep on them — no mattresses. She tells me she hand-washes them, a time-consuming task. After her shower, she reappears in a peacock-blue dress and sits on a carpet in front of me. Over tea and bread, she shares stories about her life and her country. Before we live, she offers me a fridge magnet featuring a snow leopard: “You wanted to see one, so here you go.”

At around 6pm, after showing me the bus stop for the border, Ainura and her son walk me back to Muminovoiv Guesthouse. This day turned out to be so much more than just a guided tour.